On the streets of Havana, a 1955 Chrysler New Yorker carried Ernest Hemingway to the long bar at the Floridita for daiquiris mixed strong and sour. It took him to the hilltop farmhouse where he lived most of the last twenty-two years of his life. Then it disappeared.

∞

History sometimes travels on wheels.

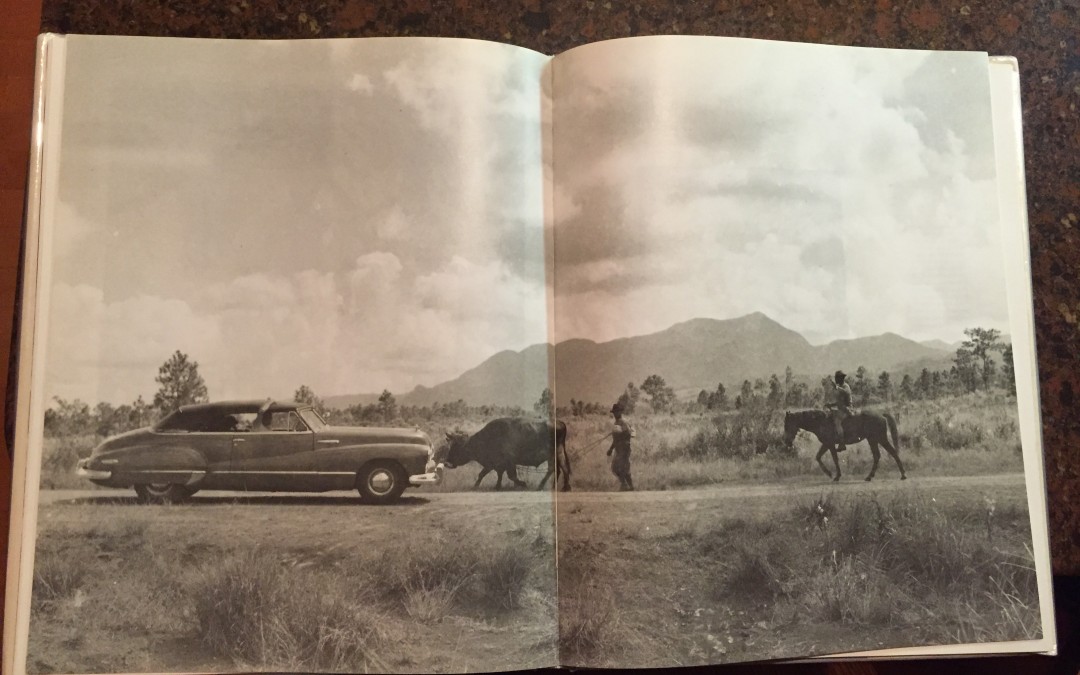

A silver Porsche steered James Dean into legend. A pink Cadillac escorted Elvis to Graceland. On the streets of Havana, a 1955 Chrysler New Yorker carried Ernest Hemingway to the long bar at the Floridita, which he called “the best bar in the world,” for daiquiris mixed strong and sour. A two-door convertible with chrome details across the gunwales and an Art Deco eagle over the hood, wings spread wide, this car ushered the Nobel laureate to the fishing boat that he sailed into the blue current, which he simply called “the stream.” It took him to the hilltop farmhouse where he lived among royal palms and mango trees most of the last twenty-two years of his life.

Then it disappeared.

For decades, Hemingway’s car survived only in legend. Was it still on the island? Had it been secreted away? Or was it lost to history, fallen into scrap metal? It became the automotive version of Hemingway’s missing suitcase, the one full of early manuscripts that his first wife Hadley lost in a Paris train station and never found.

“This is where Hemingway lived for twenty-one years and this was where he felt at home,” said Christopher P. Baker, a British writer who had long been on the trail of the vehicle himself.

“His homeland was the United States, but his home was Cuba. He’s revered here. His books are essential reading in school. They teach here that he sided with the revolution. That’s never been proven. But everybody who comes here wants a mojito and daiquiri. That’s de rigueur. How many places in the world have so many associations with Hemingway? That’s the whole mythology about Hemingway’s Cuba.”

Baker heard the first hint about the car back in 1996 from an American who believed he was buying the legendary auto. “Somebody was selling him a joke,” Baker said. But somewhere out there, he thought, the car must exist. In 2009, he talked with the director of Cuba’s automobile museum. He told Baker he’d seen the car, but it was “hidden away.”

The alleyways of Old Havana are still full of vintage Plymouths and Packards, cars with graceful curving hoods and rocket ship fins, relics of the 1950s, when Americans descended on Cuba for its bars, brothels and casinos. More than fifty years after Castro’s socialist revolution ended the party, those old cars linger as postcards of Cuba’s past. Some gleam like they just motored off the showroom floor. Others seem held together by rust and fading paint. Hemingway’s Chrysler was lost among these fossils.

Then one day it reappeared, but before it could find a new life, it would have to endure an adventure of real-life sleuthing, an aging TV detective and Cold War politics thawing in a new millennium.

If any bridge has connected the U.S. and Cuba despite the nations’ Cold War feud, it is Hemingway, a man who was both quintessentially American and utterly devoted to Cuba. He’s the reason tourists still pack the Floridita to snap selfies by his statue. No time has been better to revive his spirit in Cuba than now, when the two countries are flirting again. And no vehicle could be more fitting to bring him back than the Chrysler New Yorker he used to drive.

Read the full essay at Narratively.