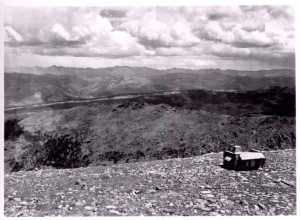

Civilian Conservation Corps laborers in 1933 work on the foundation for the Tigiwon community center, a building intended for pilgrims coming to view the Mount of the Holy Cross. US Forest Service photo.

In the midst of the Great Depression, thousands of out-of-work young men from across the country found jobs in Colorado in the Civilian Conservation Corps. The government relief program hired laborers to build roads, cut trails and raise buildings on public lands throughout the United States. Nearly eighty years later, their work can still be seen in some of the most popular trails and landmarks on the White River National Forest. Now, some of those sites are getting a little extra protection to preserve their legacy into the future. David Frey reports.

(Listen to the story here.)

[Sounds of rock chipping]The Hanging Lake trail in Glenwood Canyon is well-loved, and well-worn. It’s short – just one point two miles – but it’s steep. The big payoff comes at the end, when hikers reach a spectacular turquoise lake filled by cascading waterfalls.

“It almost feelsl like you’re in a tropical paradise once you get up to the top. It’s just a beautiful turquoise. It’s just like nothing I’ve ever seen in Colorado.” [10 sec]

Jill Wilson, from Denver, was among some one hundred volunteers clearing away boulders and building rock steps on a recent workday. The Forest Service says eighty thousand people hike the trail each year. That’s a lot of hikers. They can thank volunteers like these, from Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado and Roaring Fork Outdoor Volunteers, who are taking part in a two-year trail maintenance project at Hanging Lake. And they can thank crews from the Civilian Conservation Corps, who were doing similar work here almost eighty years ago.

[Newsreel sound]

CCC workers built this shelter house on Notch Mountain as a way station for pilgrims coming to view Mount of the Holy Cross. US Forest Service photo.

“In many parts of the country are regions which depend largely upon the tourist’s trade as the local industry. Areas of great scenic beauty have been made available to thousands of visitors through the development of roads in national and state parks and at other centers of attraction for tourists. Many of these vacation spots were completely inaccessible before the assistance of the works program made road construction possible.”

Between 1933 and 1942, the CCC hired two-point-five million young men from across the country to work in national and state parks and forests. Thousands of them came to camps in Colorado, where they planted trees, thinned forests, cut roads, and raised buildings. On the White River National Forest, CCC crews built the first ski trail on Aspen Mountain, started a ski hill in Glenwood Springs, and dug Chapman Dam above Basalt. And they built trails in places like Crater Lake, Avalanche Creek and Trappers Lake – trails that remain popular today.

“These are kids who had no skills yet and they were under instructors to learn how to build bridges and preserve the walls, stack rocks. There’s signs of CCC elements everywhere.” [10 sec]

Andrea Brogan is Heritage Program Manager for the White River National Forest.

“The forest benefited from their hard work. I think the kids benefited from the experience.”

Over the decades, weather, animals and vandals have taken their toll on the cabins and shelters they built. Many have crumbled and some, like the shelter at Hanging Lake, are nearly gone. Last year, the Forest Service spent about two hundred thousand dollars in American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds to hire local contractors to restore historic CCC buildings. It was recession stimulus money shoring up projects built with depression stimulus money.

Hikers visit the shelter house on Notch Mountain, which affords a stunning view of Mount of the Holy Cross rising behind it. US Forest Service photo.

Workers last year hiked in with only hand tools, using mules to haul materials, to refurbish a shelter house atop Notch Mountain, much as CCC workers did when they first built it in 1934. With its two-foot-thick walls built of local stone, the house was built as a way station for pilgrims to view Mount of the Holy Cross. Today, many hikers come just to see the house.

Crews also repaired the rock-and-timber Tigiwon community center below, a staging area for Holy Cross pilgrims, and the Piney Guard Station, a ranger cabin north of Wolcott.

Heritage Program Manager Andrea Brogan says, like the legacy in the White River National Forest, CCC structures across the country are being renovated, partly for their historical value, and partly because many are still used and loved.

“The part they played in it is worth preserving. It’s part of fabric of the forest. As long as we can continue to be good stewards I think we have an obligation to take care of those resources.” [11 sec]

Bill Kight is the White River National Forest’s community liaison and an archeologist. For him, this preservation work is personal. His father was one of those CCC boys back in the 1930s.

“I think a lot of people who talk about socialism and all this social this and social that in a bad way don’t have a clue about what those programs did to help our country. I think that’s a shame because the record is there. It speaks for itself.”

“Once I built a tower up to the sun, brick and rivet and lime. Once I built a tower, now it’s done, brother can you spare a dime.”

Brogan is nominating both the Tigiwon community center, near Red Cliff, and the Notch Mountain shelter house, for National Historic Landmark status. If approved, they would join six existing landmarks on the forest, including the Independence town site, the Ashcroft ghost town and the Tenth Mountain Division training site at Camp Hale.

MUSIC up under copy

“Say buddy, can you spare a dime?”

MUSIC fade

For Aspen Public Radio news, I’m David Frey.