ASPEN JOURNALISM

Aspen Journalism is an independent nonprofit news organization.

Vacancy rates rose up and down the valley, due in part to a flurry of new construction followed by a disappearance of jobs. In Battlement Mesa, where vacancy rates tripled, apartments offer move-in specials. David Frey photo.

When the recession ended the boom times of the first decade of the 21st Century, it left the lights out in thousands of unoccupied homes across the Roaring Fork and Colorado River valleys.

Results of the 2010 U.S. Census show vacancy rates climbed from Aspen to Parachute, largely as a result of new construction outpacing demand after the housing bubble burst.

Vacancy rates rose sharpest in western Garfield County, where residents fled due to the recession and vanishing jobs in the gas patch. The situation was worst in Parachute and Battlement Mesa, where nearly one in three homes were left empty.

“Definitely in the state we’ve had overbuilding,” said Elizabeth Garner, state demographer with the Department of Local Affairs. “I think everyone is well aware of that now.“There’s a ton of different issues. There are a lot of people that got into second homes that shouldn’t have been in them. There are a lot of people that got into first homes that shouldn’t have been in them,” she said.

Between 2000 and 2010, vacancy rates tripled in Rifle, Parachute and Battlement Mesa. They doubled in towns from Carbondale to Silt, and in Garfield County as a whole. The county had 2,950 vacant units in 2010, up from 1,107 in 2000. Its vacancy rate soared to 12.7 percent.

Imagine a population boom and you might picture a lot of full houses. Imagine a growing vacancy rate and you might picture a lot of empty houses. The Roaring Fork and Colorado River valleys got both.

The picture is sharpest in Battlement Mesa, which saw a severe boom-and-bust cycle dictated by an explosion of oil and gas jobs when fuel prices rose, and an implosion when they fell.

“Battlement Mesa, like all the Western Slope and most of the country, was seeing a lot of demand for new housing units,” said Steve Rippy, who, as manager for the Battlement Mesa Service Association, acts as the equivalent of town manager for the unincorporated community.

Over the decade, some 720 new housing units were built in Battlement Mesa to keep up with the demand, from single-family homes to apartments, and townhouses to trailers.

Subdivisions that had remained empty for decades were built up in a hurry, Rippy said. Empty mobile home lots were rented out. By 2009, Battlement Mesa hit nearly 100 percent occupancy, buoyed mostly by gas workers, he said.

“It was pretty frequent to see a van hauling a U-Haul and these types of things for a while,” Rippy said.

Originally built by Exxon in the 1980s to house oil shale workers, Battlement Mesa found new life as a retirement community after Exxon shuttered its oil shale operations in 1982 — a day remembered as Black Sunday — and left 2,000 workers out of work. It attracted retirees with a golf course, a recreation center and warm, dry weather.

After the natural gas boom, it began attracting energy workers again. Added to that mix were upvalley residents seeking lower home prices. Many of the new residents were Hispanics, whose numbers doubled in Battlement Mesa over the past 10 years, according to census figures.

The retirement community was transforming into a blue-collar neighborhood.

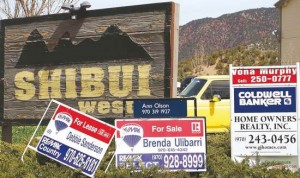

Condominiums such as Shibui West in New Castle provided housing for a growing workforce during boom times, but have emptied during the recession. David Frey photo.

Houses built, jobs vanished

“Over the last 15 years, the reality is, there were probably more people moving here who were not retired,” Rippy said.

When fuel prices fell, many gas jobs disappeared. The recession robbed others of their construction and service. Homes emptied. Construction has ground to a halt.

Now, Battlement Mesa Corp., which owns the development, is offering deals for prospective buyers to move in to apartments. Signs advertise $99 move-in specials.

“You drive through the mobile home park and you’d be shocked at how many of them are empty,” said Battlement Mesa resident Ron Roesener, who counted 11 empty homes in his own neighborhood, many of which were in foreclosure.

Across the Colorado River, Parachute experienced a similar phenomenon, only more extreme. The town saw 124 new housing units built to handle the expected growth — a big change for a town of about 1,000 people.

By the end of the decade, though, Parachute wouldn’t need any of those homes. In 2010, it had 10 fewer occupied units than it started the decade with, and 134 more vacant homes, according to the census.

The town grew by just 79 people, a 7.9 percent growth rate that was even slower than Aspen’s.

Farther up the valley, the situation only slightly improved.

Rifle went from a 3.6 percent vacancy rate to 11.2 percent.

Silt went from 3 percent to 8.4 percent.

New Castle went from 3.6 percent to 8.6 percent.

Glenwood Springs went from 4.1 percent to 8.1 percent.

Carbondale went from 4.2 percent to 8.8 percent.

The upper valley, which has a historically high vacancy rate due to a large number of second-home owners, was less affected.

Aspen’s vacancy rate grew from 33.3 percent to 40.7 percent. Basalt’s rose modestly from 13.6 percent to 16.3 percent.

Snowmass Village saw its vacancy rate decline, from 50.2 percent to 43.7 percent.